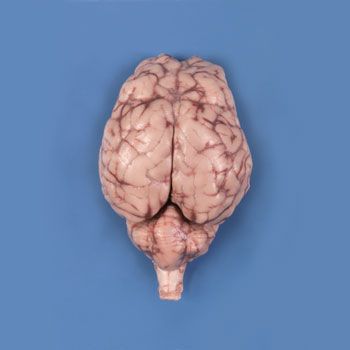

I selected the ThingLink as the digital platform for my visualization because it would allow me to annotate an image of the cortex in a way that would explain and apply the content I want students to learn. More than just wanting students to be able to identify the four lobes of the cortex , I want them to learn the processes that each region is responsible for. I created a mirror image that allowed me to add “tags” identifying and explaining each lobe of the cortex on one side, and add links to relevant articles or resources on the other. I selected the base image of the digitally rendered brain with colour-differentiated lobes because I wanted to show the boundaries between them, but I also added images within the tags that highlight that particular region within the whole of the brain. This visualization helps students see the lobes of the cortex both as discrete regions and part of a whole of the cortex. Originally I had hoped to use an actual image of a brain, but it proved difficult to find an appropriately positioned and detailed image on which I could delineate the lobes myself. Instead, I added an extra “tag” to a video in which a neuroscientist handles a brain from a recently deceased person who donated their body to science. I decided it was important to show students an actual human brain, not only for the “wow” factor, but to give a sense of scale, shape, and texture. Students might have inaccurate mental images of what an actual brain looks like, and providing an accurate image might help them create more accurate mental images as we continue to explore this unit.

preserved brains just don't "pop"

real brains don't hold their shape well

This process illuminated for me that, if it’s difficult for me (as someone who has a pretty good mental image of a human brain) to locate appropriate images and resources for students to illustrate this concept, it’s even more difficult for students to create accurate mental images. Perhaps they could get lucky and find them on their own, but that would require a significant amount of innate curiosity and motivation. In the EAA social studies program at UWM we have always been encouraged to provide visualizations to help struggling readers and/or students with gaps in knowledge. This process has made me consider the possibility that learning might sometimes have to start with the visualization and branch outward to deepen understanding, not start with other resources and use visualization as a supplement. It reminds me of a mental exercise of considering how you’d explain water to a fish: how can I explain what the cerebral cortex, the thing that arguably makes us human, to a human who has not seen one? It requires both a combination of abstract and concrete images, to give students the right conceptual image as well as an appreciation for the reality of the structure.