In designing this text set, I am considering my current group of Psychology 101 students. The class is primarily high school juniors, with some sophomores, all of whom are formally encountering psychology for the first time. The class is majority Latinx/Hispanic, split almost evenly along gender lines (14/16), and several students identify as LGBT. Student interests are diverse, the most often cited being: sports, video games, anime, and music.

These texts would be used to introduce students to the anatomy of the brain, and how people have studied and influenced it. My hope was to find a variety of texts that provide similar information in different mediums, different contexts, and with different voices. I also wanted to connect something that can be dry and somewhat intimidating to their everyday lives.

Although I don't discuss it here, one thought that has occurred to me was how these texts could be "gamified." In gamifying a text, students approach it like a puzzle, with a non-informational objective in mind. Breakout EDU is a company that sells kits that are essentially miniaturized versions of the "escape room" phenomenon. Many educators have started producing DBQs or gallery walks that contain hidden clues, which students can use to open the locks. Inside they might find candies, extra credit, or clues for yet another breakout box.

When I was first introduced to this concept I was skeptical that it would lead to learning: in the first demonstration I witnessed, students paid no attention to the content of the texts and scoured them only for superficial clues like hidden numbers or messages. However, it became clear that even if students did not actively engage with the texts at first, they were (1) being introduced to high-level texts in a non-threatening manner, and (2) their cursory glances provided them with knowledge that they could activate when revisiting the documents to complete the accompanying DBQ or gallery walk worksheet. They recognized advanced vocabulary on at least a basic level, knew where to find key information, and had gotten over any hesitation to ask questions by begging the instructor for clues to the puzzles.

In the future, I would like to design such an activity using texts like these. It allows for students to engage in a larger number of selected texts more quickly, and primes them to revisit the content on a more thorough level later. Plus, it's fun.

This video from CrashCourse contains a lot of the same information as the King textbook described above. The narrator provides a detailed overview of localization in the brain, a primer on the case study of Phineas Gage, and explores structures in brain anatomy. Covering so much content in a 12-minute video means that it goes at a fast pace, however, the tone and language used is much more informal and therefore accessible. Students have expressed before that CrashCourse videos are helpful because it gets them “to the point,” and I suspect that the more playful, casual tone is appealing.

In order to get a qualitative analysis I typed one minute of the video’s content into StoryToolz. The average grade level is 9.4, meaning that this text - despite the new vocabulary and some academic language - should be much more accessible for students. It includes many of the complex biological terminology from the King textbook.

When I first listened to the video I suspected that his rate of speech and the academic vernacular would classify this as more of a grade 11 text. However, students listen to professors who speak quickly (myself included) all day, and the benefit of YouTube videos is that they can be stopped frequently to gauge understanding. From a qualitative perspective, the addition of an audio/visual component that helps students visualize and hear correct pronunciations is very valuable. Connections are more explicit, language functions are more conventional and familiar, and the examples seem more intuitive and engaging than those seen in textbooks. It assumes little knowledge on the part of the viewer. The areas where I think the content would score squarely in the “moderately” to “very“ complex on the Achieve the CORE Rubric are vocabulary and sentence structure. The reader has a very quick, sometimes stream-of-consciousness structure to his sentences, and some vocabulary remains at a higher level by nature of the discipline.

My students really enjoy YouTube as a resource; for our semester projects, many of them included YouTube videos to demonstrate connections even though it was not required. Although educational, I think the format of the text draws implicitly upon their own interests and experience. And, at a very subtle level, I think that YouTube is valuable as an educational resource because it shows students that academic material doesn’t just come from textbooks and teachers. They spend their free time on YouTube and similar platforms, so when they see that reflected in the curriculum, I think it reinforces the message that learning is for them.

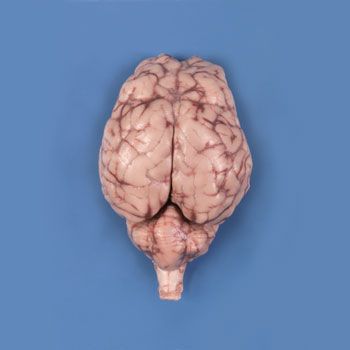

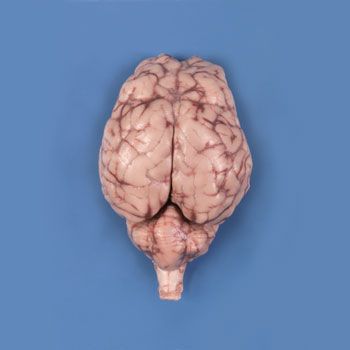

I spent a significant amount of time looking for software or models that can help students visualize and understand the anatomy of the brain. However, I can’t find anything to substitute for a specimen dissection.

I was vehemently opposed to dissection as a high school student, and would provide alternative exercises for students who did not want to view or participate in a dissection. But, giving students the opportunity to witness an instructor-led dissection and see structures “IRL” would not only bring a tactile, kinesthetic dimension in to the lesson, but it would illustrate that these are concrete, physical objects and not just concepts from readings. Students could volunteer to make incisions, identify structures as they come into view, and even hold them in their hands.

StoryToolz rates this Smithsonian article as a grade level 12.9. I feel that this is on the high side, skewed by vocabulary like trepanation, neurological, and psychosomatic. The article is short, and while it does describe ancient practices and some research dynamics that students would be unfamiliar with, they lend themselves easily to simpler explanations.

The organization, use of graphics (primarily the main image of a trepanned skull), and sentence structure are all slightly complex. The article is meant to be informational about a topic that most readers would be unfamiliar with, and by virtue of this needs to state concepts explicitly and clearly. In this way, the purpose is also slightly complex, although perhaps bordering on moderate because of the level of detail provided. This is a text that students who have no knowledge of psychology, anatomy, or ancient Peruvian culture could learn something from, provided supports for the most complex part: vocabulary.

Many of my students are very connected to their Latinx and/or indigenous heritage. Although the article linked above by no means predates Aristotle, it does demonstrate that ancient people in the Americas also made the connection between the brain, health, and behaviour. This article would serve as a good “beginner” to a lesson to emphasize the importance of the brain in many cultures, past and present.

These texts would be used to introduce students to the anatomy of the brain, and how people have studied and influenced it. My hope was to find a variety of texts that provide similar information in different mediums, different contexts, and with different voices. I also wanted to connect something that can be dry and somewhat intimidating to their everyday lives.

Although I don't discuss it here, one thought that has occurred to me was how these texts could be "gamified." In gamifying a text, students approach it like a puzzle, with a non-informational objective in mind. Breakout EDU is a company that sells kits that are essentially miniaturized versions of the "escape room" phenomenon. Many educators have started producing DBQs or gallery walks that contain hidden clues, which students can use to open the locks. Inside they might find candies, extra credit, or clues for yet another breakout box.

When I was first introduced to this concept I was skeptical that it would lead to learning: in the first demonstration I witnessed, students paid no attention to the content of the texts and scoured them only for superficial clues like hidden numbers or messages. However, it became clear that even if students did not actively engage with the texts at first, they were (1) being introduced to high-level texts in a non-threatening manner, and (2) their cursory glances provided them with knowledge that they could activate when revisiting the documents to complete the accompanying DBQ or gallery walk worksheet. They recognized advanced vocabulary on at least a basic level, knew where to find key information, and had gotten over any hesitation to ask questions by begging the instructor for clues to the puzzles.

In the future, I would like to design such an activity using texts like these. It allows for students to engage in a larger number of selected texts more quickly, and primes them to revisit the content on a more thorough level later. Plus, it's fun.

Print:

1. King, L. A. (2011). The Science of Psychology: An Appreciative View (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

This is an AP Psychology textbook. It describes the functioning of the human brain, nervous system, development, and cognitive processes. It includes transparent pages that add layers to graphics. It is unique because where most textbooks focus on abnormal psychology or what happens when systems fail, this book's stated purpose is to emphasize what happens when things to "right."

StoryToolz estimates the average grade level for this text at grade 13.3. This makes sense, considering it's an Advanced Placement text. The complex biological vocabulary and verbiage also lends itself to a higher grade level rating. Challenging vocabulary includes: differentiate, neuron, hindbrain, midbrain, forebrain, ascent, substantia nigra, dopamine, striatum, basal ganglia, reticular formation, thalamus.

Using the criterion rubric from "Achieve the CORE," I score this text as "Very Complex.” Because it is a an advanced high school-level textbook, there are some assumptions made about how students will read a textbook, especially that they will understand how headings and subheadings divide a chapter, or that key information is often emphasized in the margins. The language used to describe the location of brain structures is concrete, but relies on students having some spatial understanding of where objects exist in relationship to one another (“The thalamus is a forebrain structure that sits at the top of the brain stem). The vocabulary is expected to be unfamiliar, but the definitions also contain some overly academic language.

“The hippocampus has a special role in memory (Bethus, Tse, & Morries, 2010). Individuals who suffer from extensive hippocampal damage cannot retain any new conscious memories after the damage"

In these two sentences alone, students are assumed to understand:

- in-text citations

- that hippocampal is the adjective form of hippocampus

- the word “retain” / “retention,” which has a very different connotation in school settings

- that memories can be conscious or unconscious

The subject matter knowledge demands are very complex in that include ideas that can be recognized easily with some discipline-specific knowledge (there’s a structure in your brain called the hippocampus) with challenging abstract concepts (it plays a role in your memories, somehow).

The most redeeming aspect of this text is its use of images. Multi-layer transparencies allow students to see structures in layers, eventually adding key information and functions below the names. Short of having a physical model of the brain, this is the best representation of brain anatomy the I have found. It allows students to see structures, add additional layers to make sense of their spatial organization, and add an additional layer of information that includes key concepts & functions.

Tasks that use this text will need to be more accessible in order to compensate for some of the inaccessibility of the written text itself. It provides a lot of factual and required information that, at this time, I don’t think could be introduced in any other way: providing more detailed visual models or hands-on experience with brain structures before students have the background knowledge would be putting the cart before the horse. I think that this complexity of the text could be mitigated by utilizing many of the diagrams and transparencies that the text provides, and perhaps designing a task using a more basic Bloom's skill (identify, define, match, locate). Subsequent lessons would build upon that base layer of knowledge using texts with more accessibility, but tasks that are more challenging. The text itself, unfortunately, scores very poorly for cultural relevance. I believe that it would connect with the interests and concerns of students who are taking psychology because they are genuinely interested, or who have strong science backgrounds, but not those who take psychology because they need an elective, or other reasons. To use this text, I would draw on the experiences and interests of my students that are not contained within the text and demonstrate the connections. What is their earliest memory? Do they like haunted houses or scary movies/shows? Do they play sports or an instrument? All of these things are possible because of the structures of the brain introduced in this chapter.

2. Carter, R., Aldridge, S., Page, M., Parker, S., Frith, C. D., Frith, U., & Shulman, M. B. (2014). The Human Brain Book: An Illustrated Guide to its Structure, Function, and Disorders. NY, NY: DK Publishing.

Multimedia:

1. CrashCourse. (2014, February 24. Meet Your Master: Getting to Know Your Brain - Crash Course Psychology #4 [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vHrmiy4W9C0

This video from CrashCourse contains a lot of the same information as the King textbook described above. The narrator provides a detailed overview of localization in the brain, a primer on the case study of Phineas Gage, and explores structures in brain anatomy. Covering so much content in a 12-minute video means that it goes at a fast pace, however, the tone and language used is much more informal and therefore accessible. Students have expressed before that CrashCourse videos are helpful because it gets them “to the point,” and I suspect that the more playful, casual tone is appealing.

In order to get a qualitative analysis I typed one minute of the video’s content into StoryToolz. The average grade level is 9.4, meaning that this text - despite the new vocabulary and some academic language - should be much more accessible for students. It includes many of the complex biological terminology from the King textbook.

When I first listened to the video I suspected that his rate of speech and the academic vernacular would classify this as more of a grade 11 text. However, students listen to professors who speak quickly (myself included) all day, and the benefit of YouTube videos is that they can be stopped frequently to gauge understanding. From a qualitative perspective, the addition of an audio/visual component that helps students visualize and hear correct pronunciations is very valuable. Connections are more explicit, language functions are more conventional and familiar, and the examples seem more intuitive and engaging than those seen in textbooks. It assumes little knowledge on the part of the viewer. The areas where I think the content would score squarely in the “moderately” to “very“ complex on the Achieve the CORE Rubric are vocabulary and sentence structure. The reader has a very quick, sometimes stream-of-consciousness structure to his sentences, and some vocabulary remains at a higher level by nature of the discipline.

My students really enjoy YouTube as a resource; for our semester projects, many of them included YouTube videos to demonstrate connections even though it was not required. Although educational, I think the format of the text draws implicitly upon their own interests and experience. And, at a very subtle level, I think that YouTube is valuable as an educational resource because it shows students that academic material doesn’t just come from textbooks and teachers. They spend their free time on YouTube and similar platforms, so when they see that reflected in the curriculum, I think it reinforces the message that learning is for them.

2. Sheep brain dissection.

I spent a significant amount of time looking for software or models that can help students visualize and understand the anatomy of the brain. However, I can’t find anything to substitute for a specimen dissection.

Culturally Relevant:

1. Nuwer, R. (2013, December 20). 1,000 Years Ago, Patients Survived Brain Surgery, But They Had To Live With Huge Holes in Their Heads. Retrieved October 20, 2018, from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/1000-years-ago-patients-survived-brain-surgery-but-they-had-live-with-huge-holes-in-their-heads-180948185/

StoryToolz rates this Smithsonian article as a grade level 12.9. I feel that this is on the high side, skewed by vocabulary like trepanation, neurological, and psychosomatic. The article is short, and while it does describe ancient practices and some research dynamics that students would be unfamiliar with, they lend themselves easily to simpler explanations.

The organization, use of graphics (primarily the main image of a trepanned skull), and sentence structure are all slightly complex. The article is meant to be informational about a topic that most readers would be unfamiliar with, and by virtue of this needs to state concepts explicitly and clearly. In this way, the purpose is also slightly complex, although perhaps bordering on moderate because of the level of detail provided. This is a text that students who have no knowledge of psychology, anatomy, or ancient Peruvian culture could learn something from, provided supports for the most complex part: vocabulary.

Many of my students are very connected to their Latinx and/or indigenous heritage. Although the article linked above by no means predates Aristotle, it does demonstrate that ancient people in the Americas also made the connection between the brain, health, and behaviour. This article would serve as a good “beginner” to a lesson to emphasize the importance of the brain in many cultures, past and present.

2. Cherry, K. (2018, May 24). A Closer Look at Phrenology's History and Influence. Retrieved October 24, 2018, from https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-phrenology-2795251

A unit on the history and approaches to modern psychology would likely emphasize the musings of Aristotle and other Europeans who contemplated the nature of the mind and its relationship to the soul, the body, and illness. Non-European examples are often neglected.

In thinking about how to make sure my students see themselves and their interests reflected in the curriculum, I lamented how few non-exploitative representations there are of women and people of color in psychology. I wanted to avoid topics like eugenics and phrenology altogether, although they share a "biological basis" of sorts; students without a strong science background might not catch on to the differences between empirical science and pseudoscience without instructional time explicitly devoted to it. Instead, I've decided that introducing these ideas that perpetrated scientific racism as a "foil" to the biological bases of behaviour could be a way to engage my students' sense of social justice and dispel misconceptions.

3. Brain Differences in Athletes Playing Contact vs. Noncontact Sports. (2018, April 05). Retrieved October 23, 2018 from https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/04/180405120319.htm

4. Columbus, C. (2017, August 09). Video Games May Affect The Brain Differently, Depending On What You Play. Retrieved October 25, 2018, from https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2017/08/09/542215646/video-games-may-affect-the-brain-differently-depending-on-what-you-play

These articles could also be used as beginners, since they connect brain anatomy to interests shared by many students. My hope is that they would pique their interest and generate discussion.